Introductory Essay to Phantasmagoria, or Writer’s Whimsy

“. . . slightly horrifying and phantasmagorical. . . .”

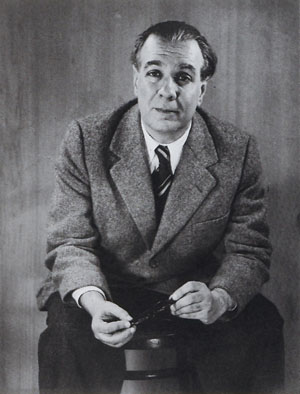

Thomas Mann on Shopenhauer, Jorge Luis Borges

T. S. Eliot famously wrote that “[n]o poet, not artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists” (37). I take Eliot to not only mean that each writer is inextricably linked to all dead writers, but also that each writer contributes to the craft with the tools of their inspirations to create something new. There is a constant passing of the torch that allows new literature to be made, but only in relation to those who have come before. Even some writers who may not at once appear related can be connected in this way. The realms of radical fantasy, weird fiction, and speculative fiction are no exception. They are arguably linked and interwoven with one another by Lord Dunsany’s influence on H. P. Lovecraft, and their subsequent influence on Jorge Luis Borges. Common tropes and motifs link their stories, such as Dunsany’s radical fantasy in creating a mythical cosmogony, Lovecraft’s subsequent adoption of this method but with a focus on personal fear, and Borges’ emphasis on sublime elements submerged in Lovecraft, such as the encounter with some grand idea or being and the character’s attempt to remedy their experience with everyday life. This is not to say that their literature is all the same; rather, each influenced the next and can be traced chronologically, which I think permits us to see how one fictional style is adapted and revised by successive authors in a sort of literary evolution of motifs.

The first writer we are to analyze is fairly obscure, even to well-read individuals, but obscurity does not imply insignificance by any means. Lord Dunsany (1878-1957) is a radical fantasist and had the misfortune of losing even his most loyal fan-base as his career aged. S. T. Joshi argues in an introductory essay for a collection of Dunsany’s work that there are three possible reasons for Dunsany’s modern-day obscurity: (I) Fantasy is “restricted in its appeal” and is hidden amidst genres like science fiction and horror, and like these genres has dealt with the “critical disdain that those literary modes suffered;” (II) that since he did not write about Ireland and was a Unionist[1] he has been overshadowed by the Irish literary revival writers, such as W. B. Yeats and George Bernard Shaw; and (III) that he simply wrote too much, and many thought that he wrote “his best work quite early in his career,” thus he lost his earlier fans and had no one to tout his work after he died (Joshi, “Introduction” to Dunsany xxii). Whatever the reasons for his obscurity, he has earned a sort of cult status for most of his stories, and in particular for his early works. Undoubtedly, Lovecraft has helped Dunsany achieve this status among today’s fantasy writers by saying of Dunsany that he is “[u]nexcelled in the sorcery of crystalline singing prose, and supreme in the creation of a gorgeous and languorous world of iridescently exotic vision” (“Supernatural Horror in Literature” 75). It is Dunsany’s creation of entire cosmoses that Lovecraft and others today praise him for, and this is mainly how he is remembered in today’s literary tradition.

I said before that Dunsany is a radical fantasist, to which I think I owe some explanation. Radical fantasy[2] is ordinarily fiction of cosmic scope and scale. Radical fantasy often includes the creation of a foreign world akin to ours but with its own imagined culture, gods, races, languages, and even including magic as a part of reality. However, the feature that distinguishes it from other types of fantasy is its cosmic scope, by which I mean the creation of a cosmos, a universe for the purpose of the story. We may see similarities between our world and one that is radically fantastic, but in radical fantasy one is asked by the writer to leave their world and universe – as much as possible – by the doorstep. A contemporary example of such literature is the popularity of Dungeons & Dragons inspired novels. For instance, the author R. A. Salvatore writes several books within a world that has been previously created and mapped out by the publisher. He then writes a compelling narrative that takes parts from this world, including the pantheon of deities and even the other worlds within the greater cosmos. Salvatore is one of several such authors employed to write in this cosmos, and one can see that such works draw much of their influence from the high fantasy of such writers as J. R. R. Tolkien but also from the radical fantasy of Lord Dunsany.

One of Lord Dunsany’s defining works is his Gods of Pegāna, which was published in 1905. It is a story that draws massive influence from Dunsany’s “thorough familiarity with the language of the King James Bible” and Greco-Roman mythology (Joshi, “Introduction” to Dunsany xi). However, the story is dissimilar to the Bible and mythology in that Dunsany is not creating a religious document or tale; the story is not a claim upon reality or seriously asserting any real deities. This story demonstrates the imperative feature of radical fantasy, that it be cosmic in scale. For example, Dunsany writes, “Some say that the Worlds and the Suns are but the echoes of the drumming of Skarl, and others say that they be dreams that arise in the mind of MĀNA” (4). MĀNA is responsible for all of creation because he dreams it, and he sleeps only as long as Skarl beats his drum. It is easy enough to see how this serves as a creation myth, much like God in Genesis brings the world into existence over seven days. But it is more massive in scale because MĀNA does not create only a world; rather, he creates existence instantaneously, whereas the God of Genesis creates each part of existence procedurally. From MĀNA’s dreams everything comes to be suddenly, including the pantheon of gods who play while MĀNA slumbers.

It is these gods – whose existence is only caused by MĀNA-YOOD-SUSHĀĪ’s dreams – that take the cosmos and form it into worlds and peoples:

When MĀNA-YOOD-SUSHĀĪ had made the gods there were only the gods, and They sat in the middle of time, for there was as much Time before them as behind them, which having no end had neither a beginning. . . .

Then said the gods, making the signs of the gods and speaking with Their hands lest the silence of Pegāna should blush; then said the gods to one another, speaking with Their hands: “Let Us make worlds to amuse Ourselves while MĀNA rests. Let Us make worlds and Life and Death, and colours in the sky; only let Us not break the silence upon Pegāna.” (Dunsany 5)

The gods create the worlds and suns expressly for the purpose of amusement while MĀNA sleeps. This is an aspect that helps to define Dunsany’s writing as radical fantasy because he creates an entire cosmos and then, from that very broad framework, focuses in on how certain objects come to exist in Pegāna. Dunsany’s most impressive feat is writing a work that takes on an entire cosmos, much like how mythologies throughout the world’s unique cultures have all organized cosmological schemas. For example, in Greco-Roman mythology there is a god to explain everything, from Zeus as thunder to Diana as the moon. However, Dunsany does not claim that his fantasies can explain our actual world. Joshi is clear on this point:

What Dunsany had done was to create an entire cosmogony, complete with a pantheon of ethereal but balefully powerful gods – a cosmogony, however, whose aim was not the fashioning of an ersatz religion that made any claim to metaphysical truth, but rather the embodiment of Oscar Wilde’s imperishable dictum, “The artist is the creator of beautiful things.” For Dunsany, who was probably an atheist, the creator god MĀNA-YOOD-SUSHĀĪ was not a replacement of either the jealous god of the Old Testament or the loving god of the New, but a symbol for the transience and ephemerality of all creation. (“Introduction” to Dunsany x)

The only aim Dunsany has is to create the largest universe his imagination can, hence the term radical fantasy. He acknowledges that what he creates is only fiction, like we now treat most of the world’s mythologies; he does not think that his creations are real.

It is important to view Dunsany in light of Wilde’s aesthetics. In “The Decay of Lying,” Wilde writes, “As long as a thing is useful or necessary to us, or affects us in any way, either for pain or for pleasure, or appeals strongly to our sympathies, or is a vital part of the environment in which we live, it is outside the proper sphere of art” (172). Wilde seems to mean that art is innately without utility and alien; thus art is done for its own sake, not some other purpose. When art is used it ceases to be art properly speaking, and we can see that Dunsany writes as Wilde prescribes. When Lady Gregory and W. B. Yeats created the Irish Academy of Letters in 1932 they named Dunsany an ‘associate’ rather than the more prestigious ‘academician’ status, but only because to be an academician one had to write Irish-oriented work. As Joshi recounts, “Dunsany was mightily insulted that he was chosen only as an associate” (“Introduction” to Dunsany xx). However, Dunsany was fairly placed as an associate because he took up Wilde’s literary agenda, which meant nothing he wrote was about Ireland. Dunsany’s literary concern is to create a large, beautiful cosmos with no practical use in our world just for the beauty of it, otherwise – according to Wilde – his writing would cease to be proper art. This aesthetics has the side effect of giving off a pseudo-mystical tone to his writing. It is only because Dunsany pursues beautiful things in imaginary worlds that it seems mystical, but Dunsany creates beauty for its own sake, not for some revelation of metaphysical truth.

Dunsany is also one of the first radical fantasists who helped to mold the trajectory of later fantasy, and is known to have had an influence on such titans of fantasy as J. R. R. Tolkien and Ursula K. Le Guin (Joshi, “Introduction” to Dunsany ix). I am not arguing here that Dunsany is the absolute first radical fantasist because many of the world’s most ancient literature does provide a cosmic angle of some sort.[3] However, especially as we have seen in his Gods of Pegāna, there are distinct radical fantasy elements in Dunsany used in a purely fictional sense. The world’s mythologies were at least originally intended as real explanations of the world and humankind’s purpose and place. No such claims are made by Dunsany. He instead writes tales that mimic mythologies and religious works the world over. As Joshi says, “An important feature of Dunsany’s style is his singularly felicitous invention of imaginary names – names not devised at random, but carefully coined to create dim echoes of Greek, Arabic, Asian, or other mythologies, and so to convey implication of antiquity” (“Introduction” to Dunsany xiii). Dunsany is one of the authors who showed just how far the imagination can go, just how much it can create, and showed that mythology is not just something you read; you can likewise create. He is a principal participant in taking the imagination to a radical new level, and this is what caught the developing Lovecraft’s eye.

H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) himself admitted that Lord Dunsany had a significant impact on his own literature. He is quoted as having said in a correspondence, “There are my ‘Poe’ pieces & my ‘Dunsany’ pieces – but alas – where are any Lovecraft pieces?” (qtd. in Joshi, “Introduction” to Lovecraft vii). But perhaps the easiest way to elucidate how much Lovecraft idolized Dunsany is a passage from his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature:”

Inventor of a new mythology and weaver of surprising folklore, Lord Dunsany stands dedicated to a strange world of fantastic beauty, and pledged to eternal warfare against the coarseness and ugliness of diurnal reality. His point of view is the most truly cosmic of any held in the literature of any period. . . . Beauty rather than terror is the keynote of Dunsany’s work. . . . [And to] the truly imaginative he is a talisman and a key unlocking rich storehouses of dream. (76-77)

Lovecraft is bold enough to even say that Dunsany’s cosmic scope – what I called the defining feature of radical fantasy – is grander than any other writer’s. I think such a claim demonstrates Lovecraft’s love for Dunsany’s writing, and the general flattery with which Lovecraft discusses Dunsany shows us how high Lovecraft must have esteemed him. Lovecraft places emphasis on Dunsany’s cosmic outlook and then qualifies that statement by explaining that Dunsany does not use terror; rather, he emphasizes beauty. This is where Lovecraft departs, or one could say revises, Dunsany’s radical fantasy.

Lovecraft is famous not as a fantasy writer but as a master of horror and an integral part of the evolution of subsequent genres of horror in and outside of literature.[4] Horror was not defined as a genre at the time when Lovecraft and others wrote. He belongs to a literary movement known simply – and often affectionately – as weird fiction. Weird fiction is often used as a denomination for literature that uses fantasy, science fiction, and horror elements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was called “weird” because the separations between these genres had not formed until later in the 20th century. Today it is a term used to describe literature that returns to the days of Lovecraft and others, like Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood, and is unafraid of mixing various fantastic genres.[5]

Regardless of Lovecraft’s classification as a weird fictionist, Dunsany’s influence can still be vividly seen in Lovecraft’s literature despite his revisionist focus on terror. One story with clear Dunsany influence is the cosmic scale of Lovecraft’s quintessential tale “The Call of Cthulhu.” Mark Lowell writes of Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos[6] that unlike the lovely picture painted by Dunsany, Lovecraft’s “realm of myth contains only sorrow, insanity, and death; by entering it one realizes the truth of humanity’s insignificance in the universe” (48). We see here that, according to Lowell, Lovecraft does have a cosmic scale, but he focuses on how smallness, and thus obscurity, is inherent for humanity once you take up such a massive scope. Even though the characters in “The Call of Cthulhu” all go insane when they accidentally awaken the harbinger of the Old Ones, insanity happens precisely because they cannot handle the realization of their insignificance in relation to the myth they have had the misfortune to encounter. They come to know of the “loathsome shapes that seeped down from the dark stars” and to whom humanity is like a paramecium in a pond (“The Call of Cthulhu” 165).

The pseudo-mystical elements of Dunsany also carry over in thematic ways, such as in Lovecraft’s very short story – one may even argue a flash fiction piece – “Nyarlathotep.” The story ends in a climax where the titular Old One, Nyarlathotep, allows the narrator a glimpse into the terrible reality of the cosmos:

Screamingly sentient, dumbly delirious, only the gods that were can tell. . . . Beyond the worlds vague ghosts of monstrous things; half-seen columns of unsanctified temples that rest on nameless rocks beneath space and reached up to dizzy vacua above the spheres of light and darkness. And through this revolting graveyard of the universe . . . dance slowly, awkwardly, and absurdly the gigantic, tenebrous ultimate gods. . . . (“Nyarlathotep” 33)

This fits into a mystic schema in that an inconceivable gift of knowledge is given to the narrator, a sort of revelation that shows the unreality of reality. We are shown temples that somehow are “beneath space,” as if outside of reality, and the narrator relates also that all this is shown to him in “inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond Time” (“Nyarlathotep” 33). Revelation and a disproval of common elements of reality, like time and space, I would argue share the pseudo-mysticism that we find at the end of Gods of Pegāna. This pseudo-mysticism is a result of Dunsany taking up Wilde’s aesthetics,[7] and this system of aesthetics seems to be picked up by Lovecraft – though his task is terror as opposed to beauty.

Lovecraft revises Dunsany by supplanting beauty with horror, as we have said, but it is how he does this, the way he plays with perspective, that makes his work not just revisionary but visionary. Whereas Dunsany tells his tales from the third-person, Lovecraft uses first-person to give the reader a more experiential perspective of the story. S. T. Joshi says that “[o]ne of the chief ways Dunsany conveyed [his] topos was by the use of a nonhuman perspective” (“Introduction” to Dunsany xvii). I agree with this assessment, and I think it is shown in how the entirety of the Gods of Pegāna is narrated from a god-like perspective. For example, the entire story begins, “In the mists before the Beginning, Fate and Chance cast lots to decide whose Game should be; and he that won strode through the mists” (Dunsany 3). Though we may presume that somebody is recounting this mythology, we do get the feeling of witnessing the creation of the cosmos, which is indubitably impossible to be witnessed from a human perspective. The effect of this third-person mythology is that we feel somehow at home with the cosmos because we know how it all came to be and how it all will disappear; we partake in the delusion that we ourselves are, as we read, deities outside of time and space and thus separate from the inexorable demise of the cosmos. In reading Dunsany, we feel the impunity of the divine, for in many ways we are MĀNA-YOOD-SUSHĀĪ. In both Lovecraft and Dunsany, the cosmos will at one point cease to exist. However, we have two separate perspectives on that demise. In Lovecraft we are vulnerable to that demise because we feel present inside the cosmos, a product of the first-person narration. Opposite to Lovecraft, Dunsany allows us to be godly as a result of the third-person narration, and thus to exist outside of the cosmos and its sphere of influence. Since we are external to the cosmos in Dunsany, we do not feel the vulnerability and the terror of the imminent and unavoidable decline of the cosmos that is so integral to Lovecraft’s task in inverting the human-centric construction of the classical monomyth.

Lovecraft’s perspectival use of the first-person has a tremendous effect on how we as the reader come to see the cosmic. One almost immediate consequence of Lovecraft’s revision is that the narrator cannot fully comprehend events because the cosmic is simply too immense: “The Thing cannot be described – there is no language for such abysms of shrieking and immemorial lunacy, such eldritch contradictions of all matter, force, and cosmic order” (“The Call of Cthulhu” 167). This allows Lovecraft to really take advantage of one of humanity’s fundamental fears: not knowing – or more precisely, not being able to know. Because he writes in the first-person, he can capture the psychological trauma of the cosmic, and it would be very hard for Lovecraft to inspire as much fear in his readers if he did not use the first-person in this way. For instance, an integral part of this sentence’s fear-factor is produced by relying on the narrator’s self-admitted apprehension: “When twilight came I had vaguely wished some clouds would gather, for an odd timidity about the deep skyey voids above had crept into my soul” (“The Colour Out of Space” 198). Self-reportage allows us to feel closer to the horror of the story in a way that the inhuman third-person of Dunsany would not do as well to evoke. Not only that, but we are finite, mortal, and vulnerable to the demise of the cosmos. We are within the fictional universe rather than a divine onlooker, such as we are in Dunsany. The immediate effect of this is the overwhelming dread of death, for in Lovecraft we exist within the story and without comfort.

An aspect of Lovecraft’s inclination toward the first-person perspective is that his stories are often self-aware in that they are cognizant that they are being read. This allows for a subtle meta-level soliloquy for the reader to enjoy. We see this in “The Call of Cthulhu” when the narrator says, “I have looked upon all that the universe has to hold of horror, and even the skies of spring and flowers of summer must ever afterward be poison to me” (169). The narrator speaks to the reader to tell them the result of his encounter with the cosmic – in this case, witnessing Cthulhu in the flesh – and to explain what it has done to him in the present and predictable future. However, the most explicit direct-address is in a short piece called “Dagon” where the narrator starts the story by explaining his current state: “I am writing this under an appreciable mental strain, since by tonight I shall be no more. . . . When you have read these hastily scrawled pages you may guess, though never fully realise, why it is that I must have forgetfulness or death” (1). Lovecraft’s narrator here directly calls to the reader as he prefaces his own tale, and I think that this person-to-person quality of his writing locks the reader’s attention. It is effective in doing this because we are not accustomed to reading stories that include ourselves. When the narrator speaks to ‘you,’ it makes you known and even breaks the subtle illusion that the story you read is another world. You are part of the story, and in a Lovecraft tale this inevitably means that you might be next.

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) was no secret admirer of Lovecraft. In fact, Borges wrote a story in the style of Lovecraft entitled “There Are More Things,” a title which can be read in two general ways: (I) conversationally, as if someone told you there are more things to talk about, and (II) philosophically, i.e. there are more beings in an ontological sense. Borges does not partake in the Cthulhu Mythos in this story, unlike other Lovecraft admirers; rather, he writes in the style of early Lovecraft, which does not focus on the cosmic per se. The earlier Lovecraft pieces, such as “Herbert West – Reanimator” or “The Picture in the House,” are more tactile in their horror and less preoccupied with events beyond the concrete terrors directly in their presence. In these earlier pieces, Lovecraft can be seen playing, so to speak, with the arcane, but within the confines of domestic New England storytelling. For example, whereas in “The Dunwich Horror” Lovecraft has an agenda to unveil one of his principle cosmic evils, the Old One named Yog-Sothoth,[8] in “The Picture in the House” no such agenda can be located. Instead, “The Picture in the House” demonstrates Lovecraft’s experimentation with insanity as a result of an encounter, yet it does not tread into the cosmic nuances that his stories like “The Call of Cthulhu” or “The Colour Out of Space” dare to do.

Borges could be interpreted as writing with the intent to represent both Lovecraft’s cosmic and tactile horror styles. For example, we writes, “Around dawn, I dreamed about an engraving that I had never seen before or that I had seen and forgotten; it was in the style of Piranesi, and it had a labyrinth in it” (“There Are More Things” 55). I think this is a direct homage to “The Call of Cthulhu” and how that story is started by the enigmatic dreams sent by Cthulhu to taunt humans into unleashing him upon the world. This link is made especially strong since in that story Cthulhu is first encountered in sketches and then in small sculptures. In both cases, art is the vehicle with which dreams impact the dreamer. We also see in “The Picture in the House” an engraving that, when discovered, serves as the inciting incident of the story: “On the butcher’s shop of the Anzique cannibals a small red splattering glistened picturesquely, lending vividness to the horror of the engraving” (42).

“There Are More Things” also utilizes Lovecraft’s focus on a first-person encounter with something enigmatic and incomprehensible: “None of the meaningless shapes that that night granted me correspond to the human figure or, for that matter, to any conceivable use.[9] I felt revulsion and terror. . . . I did not hear the least sound, but the presence there of incomprehensible things disquieted me” (58). Here we see Borges’ narrator reacting to the oddity of his experience, and he even outright says that he feels revulsion and fear. In the cosmically oriented Lovecraft, revulsion and fear are not one and the same, as one can go insane from terror and the incomprehensible, but revulsion belongs more to the earlier, more tactile works he wrote. In this way, I think we can see Borges tries to incorporate the mélange of Lovecraftian literature into a single short story. We can also see from this quote that Borges’ story serves as a homage to Lovecraft’s style of eliciting horror through a sort of vagueness and mystery, akin to when the characters in Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness look back at their pursuer and can only express their horror at what they see, yet they cannot explain what they saw: “It crippled our consciousness so completely that I wonder we had the residual sense to dim our torches as planned, and to strike the right tunnel toward the dead city” (334). Though in Borges’ story the narrator does not claim to have been crippled, as Lovecraft’s narrator does, this is mainly because Borges’ plays with the typical form of Lovecraftian tales, in which an encounter occurs and then the narrator reflects – as we see in the above quote – upon the sublimity of said encounter. “There Are More Things,” however, ends instead with the imminence of a true encounter and an emphasis on a key Lovecraftian theme: the temptation of knowledge, which leads to insanity (59).

Outside of Borges’ “There Are More Things” we can still see some ways in which he shares and revises motifs employed by Lovecraft. Among the most crucial of these is the central role in their stories’ plots that a fictional book assumes. Lovecraft employed the Necronomicon in many of his stories including “The Thing on the Doorstep” and “The Dunwich Horror” (343, 222). It is an imaginary book often studied by the characters in Lovecraft’s stories, which inevitably leads them down a path toward dangerous knowledge and an encounter with the Old Ones. For example, in “The Dunwich Horror” studying this book leads to an encounter with Yog-Sothoth that scars Arkham (243-244). Though I do not think Lovecraft thought literature an evil since he was a writer by trade, he chooses to use these books to unlock realms of imagination that almost exclusively cause terrible events to unfold. In his literature, language consumes the readers, and perhaps he means to show that horror is primarily a reality of the imagination, of the mind, and something to be enjoyed in stories precisely because we do not have these cosmic or supernatural horrors in real life. Here we are best reminded that Lovecraft is using his motifs as a rejection of the monomyth and of religious mythologies in general. As S. T. Joshi writes, “Lovecraft’s pseudomythology brutally shows that man is not the center of the universe, that the ‘gods’ care nothing for him, and that the inhabitants of earth and all its inhabitants are but a momentary incident in the unending cyclical chaos of the universe” (“Introduction” to Lovecraft xvii). This is Lovecraft’s motivation in the Cthulhu Mythos tales. The imaginary books he uses, like The Necronomicon, are motifs he repeatedly utilizes toward this end.

Borges also has imaginary literature, but his literary agenda is not to terrify like Lovecraft but to instead invoke intellectual awe. In this way Borges may be said to split the difference between Lovecraft’s horror and Dunsany’s sublime beauty. For example, in “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” the narrator seeks and finds a mysterious article on Uqbar, a place only mentioned in a specific volume of The Anglo-American Cyclopedia. He continues his research and finds that “the literature of Uqbar was fantastic in character, and that its epics and legends never referred to reality, but to the two imaginary regions of Mlejnas and Tlön” (“Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” 19). The narrator then continues to try to find knowledge on Uqbar and its literature, which ends up entrapping him in the idealism of Tlön and to the research of this imaginary world. Of course, the negative and horror-driven endings of Lovecraft tales do not show up in “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” because Lovecraft’s and Borges’ literary motivations are not identical. However, Borges’ does show us how even an imaginary series of worlds can trap the human mind, how perhaps reality and unreality are both merely categories of means of evaluation, i.e. real things are tangibly observed, but unreal things can be analytically treated by the imagination. For instance, this theme can be demonstrated when objects from Tlön begin to appear in the real world toward the end of the story in the narrator’s postscript (“Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” 30-35). They are imaginary, yet also real.

As a librarian, Borges existed within an environment that allowed him to think not only about literature but books themselves, sitting on their shelves and withholding information in such a clandestine way. The library environment appears within “The Library of Babel,” in which he writes, “On some shelf in some hexagon, it was argued, there must exist a book that is the cipher and perfect compendium of all other books” (15). He is essentially writing that in the library there is one infinite book, and whosoever reads this book become god-like. Borges, therefore, shows that he mixes his idealistic thought[10] with his library metaphysics, and the positing of an infinite book is one way in which I think Borges takes a Lovecraftian motif and readapts it for his purpose of intellectual awe. Rather than have one ever tempting book with finite knowledge, he posits a book that contains and is greater than all other books by essentially using St. Anselm’s classic Ontological Argument. One can almost imagine Borges writing this story as a direct result of looking out from the Buenos Aires Library’s balconies and applying his knowledge of literature and philosophy to the sight of all those books. “The Library of Babel” may very well be called “Descartes, Berkeley, and Bergson: Metaphysics and Ontology of the Great Library” given its mimesis of philosophical methods.

Borges’ stories also tend to share with Lovecraft the use of first-person narration. We saw how with Lovecraft his stories can often be read as a direct address to the reader. In Borges we see this as well, but in a not so formalistic manner. For example, in his story “The Aleph” the narrator always is in first-person and there is perhaps nothing out of the ordinary about this. But Borges does what Lovecraft does in “Dagon:” he directly addresses the reader. However, Borges does not follow the form Lovecraft uses where he speaks directly to the reader from the start; rather, his narrator is forced to become self-aware because of an encounter with the infinite:

[I] saw the Aleph from everywhere at once, saw the earth in the Aleph, and the Aleph once more in the earth and the earth in the Aleph, saw my face and my viscera, saw your face, and I felt dizzy, and I wept, because my eyes had seen that secret, hypothetical object whose name has been usurped by men but which man has never truly look upon: the inconceivable universe. (“The Aleph” 39)[11]

The beauty of this passage is that the narrator calls you out as the reader almost out of nowhere. You feel a sort of shock that the story has addressed you and thus included you in the plot; you are a part of the story, regardless of whether you want to be. Borges’ direct address here breaks the fourth wall very spontaneously, in a way Lovecraft never would. Breaking the fourth wall creates a world-shattering effect because the story world that the reader thinks they know is disturbed by the narrator’s ability to defy the laws with which stories normally abide. There is a sort of omnipotence portrayed by such an act because we cannot break the fourth wall in our day-to-day lives into an onlooker’s universe. It is only in art that we can tear through this wall. This links Borges to Dunsany in that they both play with a perspective of omnipotence, an experience of the infinite in which death and despair is not the byproduct of the encounter. The story manages to surprise you, circumvent your authority of choice, and demonstrate the power of an unleashed imagination. It is also interesting to see how the above narrator’s encounter with the infinite and his sorrow at this encounter parallels so well with the Lovecraftian motif of sadness and insanity when given a glimpse of the cosmos. Borges is somewhere between Dunsany’s omnipotent perspective and Lovecraft’s utterly finite perspective. He seeks in his writing more than these others to exist within the paradox of being a finite being that, via language, is capable of conceiving and encountering the infinite. Borges does not paint a misanthropic vision, which Lovecraft can be accused of, nor can he be called a fantasist who seems to reject the real world, like Dunsany was criticized by his fellow Irish writers. In Borges, there is an attempt to reconcile these two more extreme perspectives in Dunsany and Lovecraft.

Lord Dunsany and Borges share similarities, as well, and we know that Borges read Dunsany because he included one of his stories, “Carcassonne,” in his essay “Kafka and His Precursors.” Borges read Dunsany, perhaps because of Lovecraft’s praise, and they share primarily their pseudo-mystical outlook.[12] For example, in a very short story called “On Salvation by Deeds,” Borges writes about a meeting of Shinto divinities at Izumo. They meet in order to discuss their creations: Japan, the world, and man. One of them says that man has developed the art of war too far, that the nuclear bomb is too terrible a creation; therefore, “[b]efore this senseless deed is done, let us wipe out men” (“On the Salvation of Deeds” 86). The way in which these divinities meet and discuss humanity is very similar to passages in the Gods of Pegāna where the lesser gods decide the fate of the worlds they made. The mythological elements of Dunsany, which are turned upside down by Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos, are intact in this brief piece. Following this divinity’s speech that man must be destroyed, another one speaks:

It’s true. They have thought up that atrocity, but there is also this something quite different, which fits in the space encompassed by seventeen syllables. The divinity intoned them. They were in an unknown language, and I could not understand them. The leading divinity delivered a judgment: Let men survive. Thus, because of a haiku, the human race was saved. (“On the Salvation of Deeds” 86-87)

Therefore, we see how Borges yet again does not fail to place literature – in this case a haiku – as the one pure creation of humanity, similar to how he speculates the divine book in “The Library of Babel.” Literature is so good that it atones for the creation of the atomic bomb.[13]

However, Borges is more focused on philosophy than Dunsany and Lovecraft ever were. “The Library of Babel” can be read as a literary experiment in metaphysics. For example, he writes, “The Library has existed ab æternitate.[14] That truth, whose immediate corollary is the future of the world, no rational mind can doubt;” and “Man, the imperfect librarian” (“The Library of Babel” 10). These claims bring to my mind phrases Rene Descartes uses in his Meditations on First Philosophy, especially where he makes the argument that humans are finite, yet we have the idea of infinity, therefore an infinite being gave us this idea; that infinite being is God. Borges is applying such philosophical inquiry into the world of literature. This is what gives him such a unique tone in comparison to the Biblical language of Dunsany or the alliterative style of Lovecraft. His writing comes across as a serious encyclopedic entry, as if he were writing a piece for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. This scholarly tone comes across in many of his tales, definitely including “The Library of Babel,” which I think is supported by the above quotation’s seriousness and profundity.

The writing of Lord Dunsany, H. P. Lovecraft, and Jorge Luis Borges can be linked by the chronological development of themes and motifs of their works. Dunsany came first, and we can see elements of his literature, such as his radical fantasy and its creation of a cosmogony, adopted and then revised by Lovecraft. The perversion of the monomyth in Lovecraft and a focus on first-person encounters with the arcane and unknowable is then, in turn, revised by Borges into a focus on more philosophical concerns of literature and the imagination. But what is important is not simply that Lovecraft read Dunsany, or that Borges admired Lovecraft’s tales of horror. By and large, writers are influenced by their predecessors and try to exist within certain traditions while adding a touch of their own originality to their body of work. To return to T. S. Eliot’s profound point on art:

No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists. You cannot value him alone; you must set him, for contrast and comparison, among the dead. I mean this as a principle of aesthetic, not merely historical, criticism. The necessity that he shall conform, that he shall cohere, is not onesided; what happens when a new work of art is created is something that happens simultaneously to all the works of art which preceded it. (37)

What we have encountered ironically in our evaluation of Dunsany, Lovecraft, and Borges is much like the encounters with words and literature in their stories. Much as Mung merely says his name to bring about death in Gods of Pegāna, the followers of Cthulhu try to call out his unpronounceable name, or the narrator in “On Salvation by Deeds” tries to understand the haiku spoken by the Shinto deity, all of these authors’ writing exists as part of a singular art form that, while not improving, does acknowledge that “the material of art is never quite the same” (Eliot 38).

Borges himself seems cognizant of Eliot’s point. He once wrote that “[i]n the course of a life dedicated to belles-lettres and, occasionally, to the perplexities of metaphysics, I have glimpsed or foreseen a refutation of time” (“A New Refutation of Time” 61). Perhaps this line shows how Borges himself felt a certain draw toward a mystical and intuition-based refutation of time because it is somehow an aspect of literature itself. However, he does not agree with the draw of such a refutation; rather, he thinks that “[a]ll language is of a successive nature; it does not lend itself to reasoning on eternal, intemporal matters” (“A New Refutation of Time” 68). This seems to show that he agrees with Eliot that literature exists in the context of all literary traditions, that language cannot escape time because temporality is one of its defining features. Yet, the result of this reasoning is that literature and language is paradoxical in that it tends to pull one toward a refutation of time – i.e. a sort of timelessness or sub specie aeternitatis[15] – while at the same time existing within time.[16] Lovecraft, likewise, seems to understand that literature is very similar across time and that future writers do not have a duty to disown or drastically change those who came before. As he concludes in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” he says:

Startling mutations, however, are not to be looked for in [future supernatural horror]. In any case, an approximate balance of tendencies will continue to exist; and while we may justly expect a further subtilisation of technique, we have no reason to think that the general position of the spectral in literature will be altered. (82)

Indeed, writers share a commonality of art that weaves them together, and each author writes within their traditions – and even within the broader traditions of literature, and then art in general – not to mutate a genre or recast a style completely, but to use their pen and mind as a whetstone to hone traditions in their own original ways.

[1] Unionism in Ireland at this time would mean that Dunsany supported the continued union between Ireland and Great Britain, as opposed to the Nationalists who wanted Ireland to be independent.

[2] To my knowledge, I am coining the term radical fantasy in this essay as opposed to using a more common term, high fantasy, coined by Lloyd Alexander. For the purposes of this essay these two terms are not interchangeable, because high fantasy puts no special emphasis on cosmic scale the way radical fantasy does.

[3] All of the Greco-Roman mythological tales could be called a sort of radical fantasy, as could early creation myths the world over, such as the story told in Genesis or the Chinese Pangu myth.

[4] Lovecraft’s influence has undoubtedly entered popular culture. One can see his influence on writers, like Stephen King and John W. Campbell, Jr., but also on Hollywood in films like The Thing (adapted from a Campbell novella) and the Hellraiser and Alien franchises; on comic books’ cosmic villains, such as Galactus and Thanos (now a movie villain); and even on video games, like the ‘Old Gods’ in World of Warcraft and the Daedric Princes in the Elder Scrolls franchise.

[5] Lovecraft was not the first, nor was he the last, weird fictionist. For example, Lovecraft’s self-professed favorite weird tale, “The Willows” by Algernon Blackwood, of which he says “art and restraint in narrative reach their very highest development,” was published in 1907 when he was only seventeen (“Supernatural Horror in Literature” 74).

[6] Lowell explains that Cthulhu Mythos stories are not just the names associated with them, such as Cthulhu, Azathoth, and Yog-Sothoth, etc., but are at their core a “perversion of… the mythic cycle, or the monomyth… [where] a herald calls a hero into a realm of myth and the unconscious where he [or she] confronts various tribulations and emerges with a boon for” his or her comrades (47-48).

[7] See pages 7-8.

[8] Another point on Lovecraft’s influence on popular culture: One of the Old Gods in World of Warcraft is named Yogg-Saron as homage to Yog-Sothoth, meanwhile a second Old God is named C’Thun, which obviously is an allusion to Cthulhu.

[9] Since Borges says there is no use for these things, he may be alluding to Wilde’s aesthetics here: art proper cannot be useful per se. If so, this is a connection that links Borges strongly to Dunsany.

[10] Borges was very much interested and inspired in his writing by George Berkeley’s subjective idealism.

[11] Italics added for emphasis.

[12] However, since Borges admired Berkeley and the French philosopher Henri Bergson (who was accused of mysticism by Bertrand Russell), he might have been closer to a real mystic than Dunsany.

[13] The story’s location in Japan and using traditional Japanese deities is likely intended by Borges to have added significance since Japan had atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The story was also written in 1984, so it can certainly be read with the Cold War and the arms race as a contextual background.

[14] Latin: ‘for eternity.’

[15] Latin phrased famously used by Baruch Spinoza: ‘under the aspect of eternity.’

[16] For further philosophical investigation of language’s essence, see Martin Heidegger’s On the Way to Language.

WORKS CITED

Borges, Jorge Luis. “A New Refutation of Time.” On Mysticism. Trans. Suzanne Jill Levine. New York: Penguin Books, 2010. 60-78. Print.

———-. “On Salvation by Deeds.” On Mysticism. Trans. Suzanne Jill Levine. New York: Penguin Books, 2010. 86-87. Print.

———-. “The Aleph.” On Mysticism. Trans. Suzanne Jill Levine. New York: Penguin Books, 2010. 27-41. Print.

———-. “There Are More Things.” The Book of Sand. Trans. Norman Thomas Di Giovanni. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977. 51-60. Print.

———-. “The Library of Babel.” On Mysticism. Trans. Suzanne Jill Levine. New York: Penguin Books, 2010. 9-17. Print.

———-. “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.” Ficciones. Trans. Alastair Reid. Ed. Anthony Kerrigan. New York: Grove Press, 1962. 17-36. Print.

Dunsany, Lord. The Gods of Pegāna. In the Land of Time and Other Fantasy Tales. New York: Penguin Books, 2004. 3-48. Print.

Eliot, T. S. “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Perspecta 19 (1982). 36-42. Web. 5 March 2015.

Joshi, S. T. “Introduction.” In the Land of Time and Other Fantasy Tales. Ed. S. T. Joshi. New York: Penguin Books, 2004. ix-xxii. Print.

———-. “Introduction.” The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. Ed. S. T. Joshi. New York: Penguin Books, 1999. vii-xx. Print.

Lowell, Mark. “Lovecraft’s CTHULHU MYTHOS.” Explicator 63.1 (2004): 47-50. Academic Search Premier. Web. 10 February 2015.

Lovecraft, H. P. At the Mountains of Madness. The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories. Ed. S. T. Joshi. New York: Penguin Books, 2001. 246-340. Print.

———-. “Dagon.” The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. Ed. S. T. Joshi. New York: Penguin Books, 1999. 1-6. Print.

———-. “Nyarlathotep.” The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. Ed. S. T. Joshi. New York: Penguin Books, 1999. 31-33. Print.

———-. “Supernatural Horror in Literature.” Wikisource.com. Web. 3 February 2015.

———-. “The Call of Cthulhu.” The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. Ed. S. T. Joshi. New York: Penguin Books, 1999. 139-169. Print.

———-. “The Dunwich Horror.” The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories. Ed. S. T. Joshi. New York: Penguin Books, 2001. 206-245. Print.

———-. “The Picture in the House.” The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. Ed. S. T. Joshi. New York: Penguin Books, 1999. 34-42. Print.

Wilde, Oscar. “The Decay of Lying.” The Soul of Man Under Socialism & Selected Critical Prose. Ed. Linda Dowling. New York: Penguin Books, 2001. 163-192. Print.

Timeless Phantasmagoria: A Critical Introduction | Copyright 2016